Science

The Evolution of Morality: How Science Explains Ethics Without Religion

The Evolution of Morality: How Science Explains Ethics Without Religion

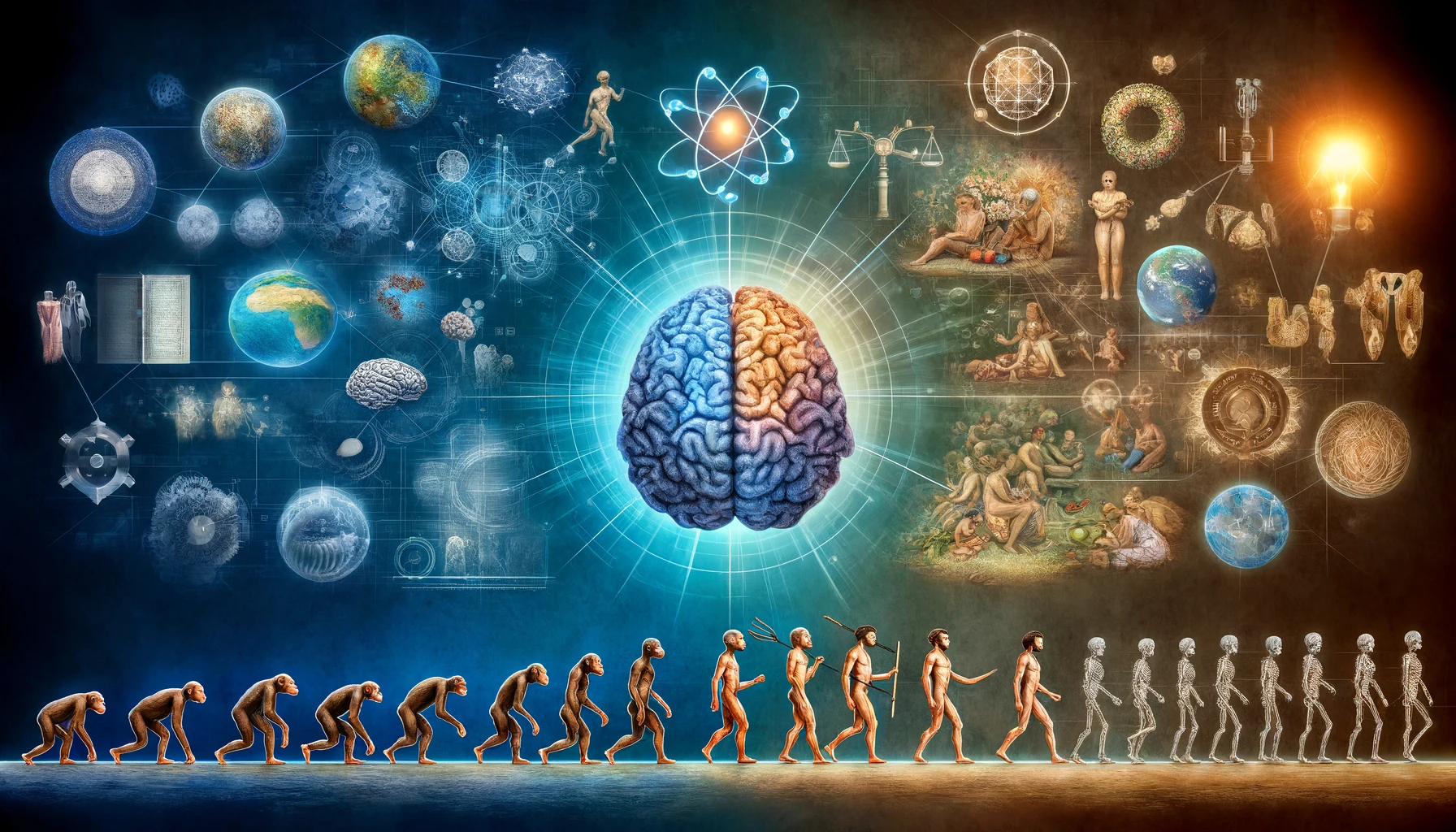

For centuries, religious institutions have positioned themselves as the ultimate arbiters of morality, asserting that ethics and morality are inherently tied to divine authority. However, contemporary scientific research challenges this notion, offering substantial evidence that morality can be understood through natural processes, such as evolution, psychology, and neuroscience. The evolution of morality reveals a complex interplay of social, psychological, and biological factors, demonstrating that morality is not exclusive to religious teachings but is instead a deeply ingrained feature of human and animal behavior. This article delves into the evolution of morality, how secular ethical systems have developed independently of religion, and what implications this has for understanding ethics in a rapidly changing world.

The Evolutionary Origins of Morality

The roots of moral behavior can be traced back to early human societies and even to other social animals. Evolutionary biologists suggest that behaviors associated with cooperation, empathy, and altruism provided a significant survival advantage to early human groups. Cooperation among members of a group often ensured that scarce resources were shared, mutual protection was offered, and the community's overall survival chances were improved. Morality, therefore, can be seen as an evolutionary adaptation that enabled human beings to thrive as social creatures.

Charles Darwin himself proposed that behaviors such as sympathy, altruism, and cooperation were not unique to humans but could be found in other social animals as well. In "The Descent of Man" (1871), Darwin argued that "any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts... would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience." According to Darwin, the social instincts of animals formed the foundation for the evolution of moral behavior—long before the advent of organized religions. The moral sense was driven by natural selection, favoring traits that fostered social harmony and group survival.

Modern studies have confirmed Darwin's observations, showing that behaviors like cooperation, empathy, and fairness are not unique to humans. For example, chimpanzees and bonobos, two of our closest primate relatives, display behaviors that suggest a basic form of morality. Chimpanzees exhibit a sense of fairness when it comes to sharing resources, and they often engage in reciprocal grooming, which strengthens social bonds within their groups. In one study conducted by Frans de Waal (2006), chimpanzees refused to accept rewards when they observed another chimpanzee being treated unfairly, suggesting that even non-human animals have an understanding of justice and fairness.

Similarly, bonobos are known for their strong social bonds, empathy, and cooperative behavior. Bonobos have been observed comforting distressed members of their group, demonstrating a level of emotional empathy that parallels human reactions. These examples suggest that the capacity for moral-like behavior is present in species that have no concept of religion, indicating that morality could have evolved as a natural response to social living—long before religious doctrines and belief systems emerged.

Neuroscience and Moral Decision-Making

Neuroscientific research has also provided significant insights into how the human brain processes moral decisions, challenging the notion that morality must come from an external divine source. Advances in neuroimaging technology have allowed researchers to identify specific brain regions involved in moral reasoning, empathy, and emotional responses to moral dilemmas. These findings suggest that moral behavior is fundamentally a product of cognitive and emotional processes in the brain rather than a response to religious teachings.

One prominent study by Joshua Greene and colleagues (2001) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine participants' brains as they responded to moral dilemmas, such as the famous trolley problem. The study found that different types of moral dilemmas activated distinct neural circuits. When faced with a decision involving direct harm to another person, participants' amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) were activated, suggesting an emotional response. Conversely, when participants made more utilitarian decisions that required a detached, logical assessment of outcomes, regions like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) were more active. This dual-process model of moral decision-making—involving both emotional and rational components—suggests that morality arises from the complex interaction of different brain systems rather than adherence to an external authority.

Antonio Damasio, a leading neuroscientist, has further explored the link between emotions and moral decision-making. In his work on patients with damage to the prefrontal cortex, Damasio found that individuals with impaired emotional responses struggled with making moral decisions, often acting in ways that were socially inappropriate or self-serving (Damasio, 1994). This research underscores the importance of emotions in shaping moral behavior and highlights how morality is deeply connected to our biology.

Secular Ethical Systems: A Historical Perspective

Throughout history, ethical systems independent of religion have emerged, providing a strong case for the development of morality through reason and philosophy. Ancient Greek philosophers were among the first to establish secular frameworks for understanding ethics. Aristotle, for example, developed a virtue-based approach to ethics, emphasizing the importance of character and the pursuit of eudaimonia (flourishing or the highest human good). For Aristotle, the key to leading an ethical life was cultivating virtues like courage, honesty, and temperance, which allowed individuals to fulfill their potential and contribute to the well-being of their community. Aristotle's ethical framework was grounded in observation, reason, and the belief that human beings are inherently social creatures, rather than in adherence to divine commandments (Aristotle, 350 BCE).

Epicurus, another influential Greek philosopher, emphasized the pursuit of happiness and the avoidance of pain as the primary goals of human life. Epicurean ethics promoted a form of hedonism that prioritized simple pleasures, friendship, and tranquility—all of which could be achieved without invoking gods or divine laws. Epicurus argued that an understanding of nature, based on empirical observation and reason, was sufficient for achieving a fulfilling and ethical life (Epicurus, 3rd century BCE).

The Enlightenment period, which began in the 17th century, marked a significant turning point in the development of secular moral thought. During this time, thinkers like Immanuel Kant and John Stuart Mill challenged the authority of religious institutions and sought to develop ethical systems grounded in human reason. Kant's categorical imperative provides a rational basis for ethical behavior, arguing that actions should be performed according to universalizable maxims—rules that apply equally to everyone, regardless of individual circumstances or beliefs (Kant, 1785). Kant's emphasis on autonomy, rationality, and the intrinsic worth of human beings formed the foundation of modern deontological ethics.

Similarly, John Stuart Mill's theory of utilitarianism provided a secular approach to morality based on the principle of the greatest happiness. Mill argued that actions are morally right if they promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people and morally wrong if they cause harm or suffering. Utilitarianism emphasizes the importance of considering the consequences of one's actions and making decisions that maximize overall well-being. Unlike religious ethical systems, which often rely on rigid doctrines, utilitarianism is adaptable and can be applied to a wide range of moral issues, making it a powerful tool for addressing the complex challenges of modern society (Mill, 1861).

Contemporary Implications of Secular Morality

Understanding morality as an evolved trait and a product of human reasoning opens up new ways of thinking about contemporary ethical issues. In an increasingly globalized and technologically advanced world, secular moral frameworks offer the flexibility and inclusiveness needed to address problems like artificial intelligence (AI) ethics, climate change, and human rights without relying on religious dogma.

For instance, the rise of artificial intelligence and autonomous systems presents significant ethical challenges, particularly regarding decision-making, accountability, and the potential for bias. Religious moral systems, which often rely on absolute rules, may not be well-suited to address the nuanced ethical questions posed by AI technologies. Instead, secular ethical frameworks, such as utilitarianism and deontological ethics, allow for the careful consideration of the consequences of AI deployment and the creation of guidelines that prioritize human well-being, fairness, and justice. For example, utilitarian principles can be used to evaluate the societal benefits and risks of AI applications, while deontological ethics can help establish clear rules for the ethical use of AI, ensuring that individuals' rights are respected.

Climate change is another pressing issue that requires a global, cooperative response. Religious frameworks often focus on the afterlife or divine authority, which may detract from the urgency of addressing environmental concerns in the here and now. Secular moral systems, on the other hand, emphasize the importance of collective well-being, future generations, and environmental stewardship. The concept of intergenerational justice, which is rooted in secular ethics, argues that current generations have a moral obligation to protect the environment and ensure that future generations have access to the resources they need to thrive. This ethical perspective aligns with scientific understanding and encourages the adoption of sustainable practices that prioritize the long-term health of the planet.

Finally, the evolution of secular morality has profound implications for human rights. The concept of universal human rights is grounded in the belief that all individuals possess inherent dignity and worth, regardless of their religious beliefs or cultural background. This idea, which emerged during the Enlightenment, has become a cornerstone of modern secular ethics and forms the basis for international human rights law. By recognizing that moral principles can be derived from human reason and empathy rather than divine authority, secular morality provides a foundation for promoting equality, justice, and the protection of individual freedoms in an increasingly interconnected world.

Conclusion

The idea that morality is intrinsically tied to religion has been thoroughly challenged by both scientific research and philosophical reasoning. Evolutionary biology demonstrates that behaviors we consider moral have deep roots in social cooperation, empathy, and the need for group survival, observable even in non-human animals. Neuroscience reveals that moral decision-making is a function of the human brain, shaped by the interaction of emotional and rational processes. Historical examples of secular ethical systems, from Ancient Greek philosophy to Enlightenment humanism, further underscore that morality can arise from human reasoning without recourse to religious doctrine. As society continues to advance, embracing a secular, rational approach to ethics allows us to address complex, global issues in a way that is inclusive, adaptable, and grounded in the shared values of human dignity and well-being.

References

Aristotle. (350 BCE). Nicomachean Ethics.

Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man. John Murray.

Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Penguin Books.

De Waal, F. (2006). Primates and Philosophers: How Morality Evolved. Princeton University Press.

Epicurus. (3rd century BCE). Letter to Menoeceus.

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293(5537), 2105-2108.

Kant, I. (1785). Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals.

Mill, J. S. (1861). Utilitarianism.

Author

Lander Compton

Creation Date

21:04 at 10/24/2024

Last Updated

23:15 at 11/26/2024