Religion

Moses and the Land of the Philistines: An Anachronism Explained

The traditional belief that Moses authored the first five books of the Bible—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy—has been a central element of both Jewish and Christian religious tradition for centuries. Mosaic authorship has served to establish the divine authority of these foundational texts, implying a direct connection between God and the laws and narratives of Israel. However, modern critical scholarship has challenged the plausibility of this traditional view by identifying numerous anachronisms within the biblical text. One of the most notable of these anachronisms is the mention of the “land of the Philistines,” which appears multiple times throughout the Pentateuch. A critical examination of historical and archaeological evidence reveals that Moses could not have known about the Philistines as a settled group in the manner described in these texts. This article delves into the historical context of this anachronism, its implications for the authorship of the Pentateuch, and the broader conclusions that can be drawn from it.

The Philistines in the Pentateuch

The Philistines are referenced multiple times in the first five books of the Bible, notably in Genesis and Exodus. For example, Genesis 21:32-34 describes Abraham making a covenant with Abimelech, who is referred to as the “king of the Philistines.” Similarly, in Exodus 13:17, God is depicted as leading the Israelites away from the “land of the Philistines” after their escape from Egypt. These references to the Philistines raise significant questions regarding the historical accuracy of these narratives if they were indeed composed by Moses.

The problem with these references becomes evident when we examine the historical timeline of the Philistines. Archaeological and textual evidence indicates that the Philistines were part of the so-called Sea Peoples—a coalition of naval raiders who appeared in the Eastern Mediterranean around the 12th century BCE, during the Late Bronze Age collapse. They eventually settled along the coastal regions of Canaan, establishing cities such as Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath. This settlement occurred several centuries after the traditional dates associated with the events of the Exodus and the supposed lifetime of Moses, which are generally placed in either the 15th or 13th century BCE. Consequently, the mention of the Philistines in the Mosaic texts is an anachronism—an insertion of a later historical reality into an earlier narrative.

Historical Context of the Philistines

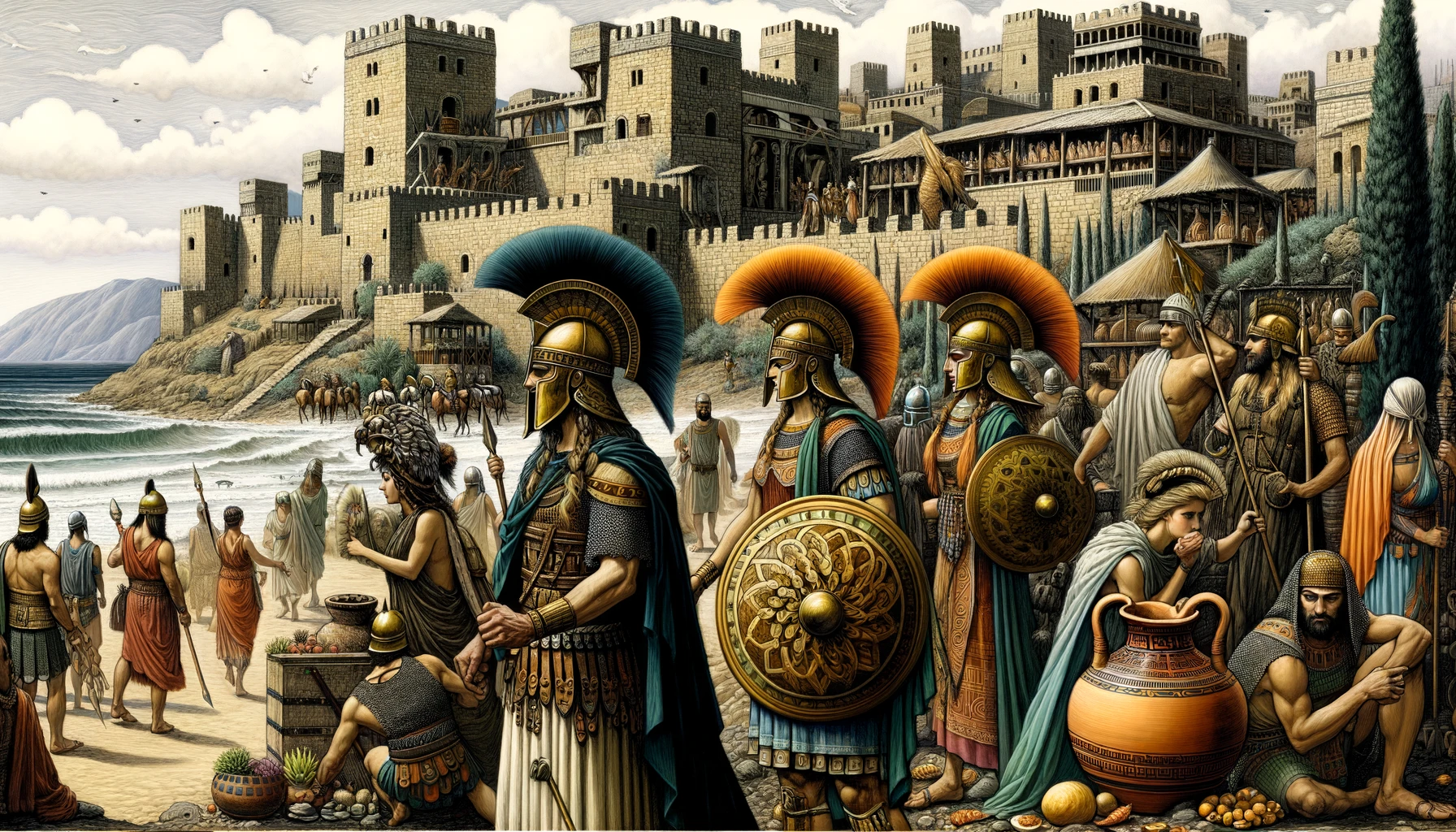

The Philistines emerged as part of the larger upheaval that characterized the Late Bronze Age collapse—a period that saw the disintegration of several major civilizations, including the Mycenaean Greeks, the Hittite Empire, and the Egyptian New Kingdom’s dominance over Canaan. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Philistines originated from the Aegean region, likely related to the Mycenaean Greeks, and established themselves along the southern coast of Canaan during the early 12th century BCE. Their material culture, including distinctive pottery styles and architectural features, exhibits clear influences from the Aegean world, setting them apart from the indigenous Canaanite populations.

By the time the Philistines settled in Canaan, the historical period traditionally associated with Moses and the Exodus would have long since passed. The Exodus is often dated to the 15th century BCE, based on a literal reading of 1 Kings 6:1, or alternatively to the 13th century BCE, based on correlations with Egyptian history, particularly during the reign of Ramesses II. In either scenario, the Philistines were not yet a settled people in Canaan during Moses' purported lifetime. Therefore, the mention of the “land of the Philistines” in Exodus 13:17 is historically incongruent, reflecting a geopolitical reality that emerged only in the subsequent Iron Age.

Anachronistic References in Genesis

The references to the Philistines in Genesis 21 and Genesis 26, during the time of Abraham and Isaac, present an additional and significant anachronism. According to the biblical chronology, Abraham and Isaac lived centuries before Moses, placing them even further back in time—likely in the early 2nd millennium BCE. The Philistines, as a recognizable group with established settlements, simply did not exist at that time. The biblical text’s reference to Philistine kings such as Abimelech suggests that the narrative was shaped or edited by writers or redactors who lived during a period when the Philistines were already familiar figures in the region.

It is highly probable that the authors or editors of these texts, compiling the narratives during the Iron Age, retrojected the presence of the Philistines into earlier patriarchal stories. By the time these texts were written or compiled, the Philistines were well established as a significant group along the coast of Canaan. Their inclusion in earlier narratives may have been intended to make the stories more relatable to contemporary audiences who would have been familiar with the Philistines as a prominent people in the region.

These anachronistic references serve as a clear indication that the narratives of Genesis were not static but were subject to ongoing editorial revision. These revisions aimed to align the stories with the sociopolitical realities of the Iron Age, reflecting the concerns of the communities that produced and preserved these texts. The process of retrojection—where later historical circumstances are projected back into earlier narratives—demonstrates that the biblical text underwent considerable revision by authors seeking to provide a cohesive and familiar context for their contemporaries.

The Documentary Hypothesis and Later Editorial Activity

The anachronistic references to the Philistines lend strong support to the Documentary Hypothesis, which posits that the Pentateuch is a composite work derived from multiple sources—commonly designated as J (Yahwist), E (Elohist), P (Priestly), and D (Deuteronomic). Each of these sources reflects distinct historical contexts, theological perspectives, and editorial interests. The presence of the Philistines in the patriarchal narratives and in the story of the Exodus suggests that these texts were shaped by authors or editors who lived during the Iron Age, long after the time of Moses.

The inclusion of the Philistines is consistent with a broader pattern of editorial activity that sought to make ancient stories comprehensible and relevant to later audiences. By including references to groups and places well known to Iron Age readers, the editors aimed to create a sense of continuity between the ancient past and the socio-political realities of their own time. This process of retrojecting later realities into earlier narratives was not unique to the Bible; it was a common practice in ancient historiography, where authors frequently updated older stories to reflect contemporary political and social conditions.

Moreover, the Documentary Hypothesis suggests that the Pentateuch was not the product of a single author but rather the result of a complex and multilayered editorial process that spanned centuries. The Yahwist and Elohist sources, for instance, are thought to have originated during the early monarchic period, while the Priestly and Deuteronomic sources were likely composed during the Babylonian Exile or shortly thereafter. The references to the Philistines in Genesis and Exodus likely entered the text through the Yahwist and Elohist traditions, which were influenced by the geopolitical realities of the Iron Age, when the Philistines were a significant presence in the coastal regions of Canaan.

From a secular perspective, the process of editing and compiling these sources reflects the historical and cultural concerns of the communities that produced them. The editors sought to create a unified narrative that connected the patriarchal past with the later history of Israel, including the period of the Judges and the early monarchy. By including references to the Philistines, the editors provided a narrative bridge that linked the ancestral stories of Abraham, Isaac, and Moses with the experiences of the Israelites during the Iron Age. This editorial strategy helped to establish a sense of historical continuity and legitimacy, reinforcing the idea that the Israelites' struggles with the Philistines were part of a much older and divinely ordained history.

Implications for Mosaic Authorship

The references to the Philistines in the Pentateuch present a significant challenge to the traditional belief in Mosaic authorship. If Moses lived in the 15th or 13th century BCE, he could not have known about the Philistines as a distinct group inhabiting the coastal regions of Canaan, as they only arrived in the region during the 12th century BCE. This discrepancy strongly suggests that these texts were composed or edited by individuals who lived during a later period, when the Philistines were already a well-established presence in Canaan.

The implications of this conclusion are profound. If the Pentateuch contains references to historical realities that postdate Moses, it is highly unlikely that Moses was the sole author of these texts. Instead, the Pentateuch appears to be a compilation of various traditions, stories, and laws that were assembled and edited over several centuries. This understanding aligns with the broader scholarly consensus that the Pentateuch is the product of a long and complex process of composition, involving multiple authors and editors working across different historical periods.

Furthermore, the presence of anachronisms such as the Philistines indicates that the biblical text was a living document, continually revised and updated to reflect the changing historical and social contexts of the Israelite community. This process of revision allowed the text to remain relevant and meaningful to successive generations, who saw their own experiences reflected in the stories of their ancestors. The editors' decision to include references to the Philistines demonstrates their effort to connect the foundational narratives of Israel with the contemporary realities of Iron Age society, thereby creating a sense of continuity and shared identity.

From an atheistic perspective, these observations reinforce the idea that the Bible is a human-created document rather than a divinely dictated text. The presence of anachronisms, along with the evidence of multiple sources and editorial activity, suggests that the Bible was shaped by human hands, reflecting the historical, cultural, and political circumstances of the people who produced it. The biblical narratives were adapted and reinterpreted to meet the needs of different communities over time, resulting in a complex and evolving text that mirrors the experiences and aspirations of ancient Israelite society.

Conclusion

The mention of the “land of the Philistines” in the Pentateuch exemplifies an anachronism that challenges the traditional view of Mosaic authorship. Historical and archaeological evidence demonstrates that the Philistines did not settle in Canaan until the 12th century BCE—long after the time of Moses. The presence of the Philistines in the narratives of Genesis and Exodus indicates that these texts were written or edited by individuals who lived during the Iron Age, when the Philistines were well known as a part of the region’s geopolitical landscape. This anachronism, alongside others found in the Pentateuch, supports the conclusion that these texts are a composite work shaped by multiple authors and editors over time. Understanding the historical context of these references provides a deeper appreciation of the complex development of the biblical narrative and challenges us to reconsider long-held assumptions about the origins of these foundational texts.

The implications of recognizing these anachronisms extend beyond the question of authorship; they invite us to understand the Bible as a dynamic and evolving document that reflects the historical experiences, cultural influences, and theological perspectives of the communities that produced it. By examining the ways in which later editors and redactors shaped the biblical text, we gain insight into how the Israelites understood their history, their relationship with their gods, and their place in the broader ancient Near Eastern world. The reference to the Philistines in the Pentateuch is just one example of how the biblical text has been shaped by the hands of many, each contributing to the rich tapestry of stories that continue to inspire and inform human thought to this day.

References

-

Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press, 2001.

-

Coogan, Michael D. The Old Testament: A Historical and Literary Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Oxford University Press, 2017.

-

Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Eerdmans, 2003.

-

Kitchen, K. A. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Eerdmans, 2003.

-

Friedman, Richard Elliott. Who Wrote the Bible? HarperOne, 1997.

-

Van Seters, John. Abraham in History and Tradition. Yale University Press, 1975.

-

Collins, John J. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Fortress Press, 2014.

-

Ska, Jean-Louis. Introduction to Reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns, 2006.

-

Carr, David M. The Formation of the Hebrew Bible: A New Reconstruction. Oxford University Press, 2011.

-

Knoppers, Gary N. Rewriting Ancient Israelite History. Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Author

Lander Compton

Creation Date

22:07 at 11/05/2024

Last Updated

22:07 at 11/05/2024